Insect Spotters Guide

Take a look at our guide to spotting some interesting invertebrates this summer!

Silver Studded Blue – Rare heathland species on wing from June to late August.

The Silver Studded Blue is a small butterfly found on heaths and sand dunes in the UK. Males have vibrant blue upper wings with a dark border while females have brown upper wings with a row of red spots on the hind section. Adults can be seen from early July through to the end of May. Caterpillars feed on heathers and gorses found on the heathland and dune areas they inhabit. Keep an eye out for them around Dawlish Warren and The Pebblebed Heaths.

Common Emerald Damsel Fly– Common – April to August

Common but declining in the UK. The Emerald Damselfly favours still water ponds bordered by tall vegetation like rushes and sedges. They can be seen on the wing between May and October. Dark, narrow wing spots distinguish these from other emerald species.

Golden Ringed Dragonfly – Common – May to September

A striking and large dragonfly the Golden Ringed Dragonfly is associated with acidic streams and heathlands. They are the longest dragonfly species in the UK with males reaching 74mm and females reaching 84mm. Their bold black and yellow banded bodies make them easy to identify and they are known for their aerobatics and high flying.

Bat-like and historically known as the “Goat Sucker”, Nightjars are a bird shrouded in mystery and an endangered species in the UK. Read more to learn about some of their interesting biology and breeding behaviour, how best to see them and how to look after them when you visit the heaths.

This mysterious bird is occasionally heard and rarely seen! Nightjars are largely nocturnal, hunting and calling late in the evening and resting during the day. They are a migratory species, spending the winter in sub-saharan Africa and the summer breeding on heathland areas in Europe. Although globally nightjar numbers are high, the species has seen significant declines in north west Europe and is listed as a cause for concern in the UK.

Nightjars are particularly susceptible to disturbance, especially by dogs. They nest in open patches of ground within the heather and gorse, hardly constructing a nest at all. They lay and incubate their eggs on a scraped patch of bare earth - for this reason it is vitally important that dogs are kept on paths and out of the heather when visiting the Pebblebed Heaths – even if a dog has no interest in the birds, they may still cause the Nightjars to abandon their nest. Eagle-eyed predators can be waiting for their chance to raid unguarded eggs when parent birds have been “flushed” off the nest.

The best time to see Nightjars is late in the evening around sunset. Head onto the heaths and listen out for male birds ‘churring’. Nightjars are territorial, males will fly between high pieces of vegetation around the nest making their distinctive call. They feed mainly on insects while in flight and have excellent night vision, similar to that of an owl. Specially adapted “whiskers” at the edges of their mouths help catch and funnel prey into their mouths.

Female Nightjars only lay one or two eggs, hatching after 2 – 3 weeks and leaving the nest (fledging) after 16 – 17 days. The female will stay with the chicks after hatching, keeping them warm and protecting them from predators. Both parents feed the chicks until they are ready to leave the nest. Survival rates of eggs to hatching may be relatively low, but once hatched, the survival rate to fledging is higher. For this reason it is particularly important to limit disturbance to nesting sites and reduce the likelihood of parents abandoning the nest. It’s always best to keep to established paths when visiting the heaths as this limits disturbance.

During the summer there’s no better way to spend an afternoon than out on the water enjoying the estuary. The Exe is a busy place with a huge variety of craft, from large fishing trawlers and yachts to stand-up paddle boarders and kite surfers, as well as internationally important wildlife. With so much going on it’s important to do some research before you head out!

Staying safe in the water – While the estuary can be a great place to explore, it is a busy area of water with a lot going on. Check the tide times and wind before going out – paddling against the tide can either be hard work or impossible. The tide can move as fast as 6 Knots and represents a real hazard for kayakers, canoeists and stand up paddle borders.

The speed limit in the estuary is 10 Knots, this applies to all craft and extends to the safe water buoy. Jet Skis (Personal Water Craft) are best used outside of the estuary away from moored boats and swimmers.

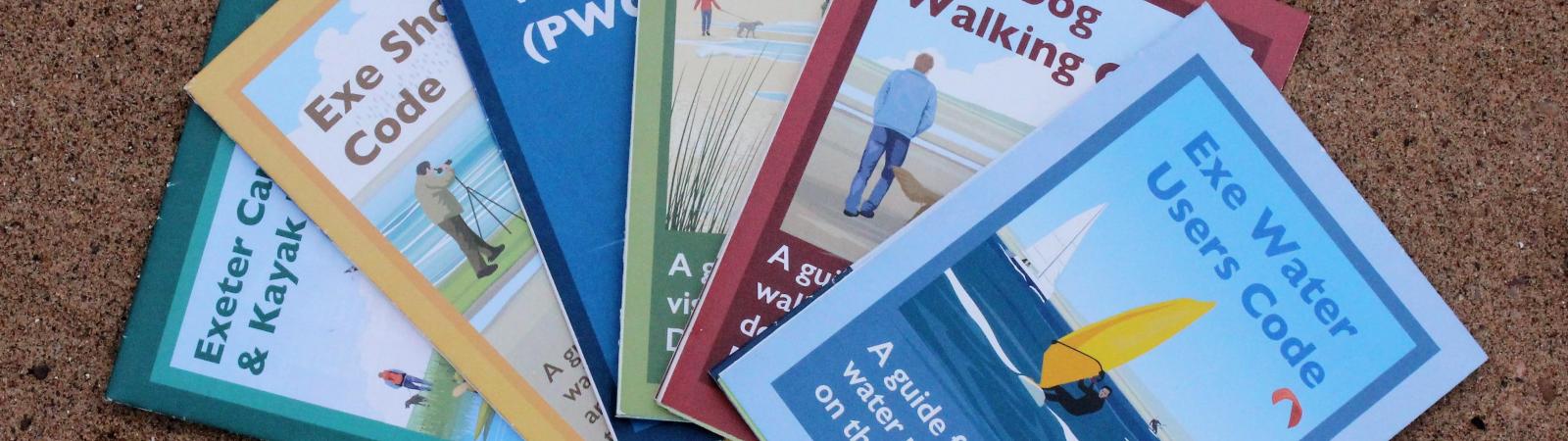

For more information check out our codes: Exe Estuary Codes | South East Devon Wildlife

Wildlife on the River – Although the largest numbers of birds can be seen during the winter months, there is still plenty to see in the estuary. Some oystercatchers will stay right through the summer because they were not fit enough to migrate or too young to breed.

Winter residents will also return sooner if their breeding has been unsuccessful, so keep an eye out for the first Brent Geese to return towards the end of the summer. On a warm day you might even see a seal or two on the sand bank.

The wildlife refuge behind Dawlish Warren applies all year round and is marked by a line of yellow buoys from the edge of the landing zone on the Warren across to Cockwood steps on the west bank of the river. The refuge restricts access to all crafts and persons at any state of the tide as these mudflats are an important food source and resting area for the protected species on the river all year round.

August saw the return of Heath Week celebrations on the East Devon Pebblebed Heaths and we hosted a Heath Week Hub at a different site every day. It was great to speak to so many people about the ecology and history of our local heathland. We even had a Nightjar specimen on tour with us which was greatly appreciated by everyone that stopped by - you don’t normally get a close up look at such an elusive species!

I particularly enjoyed a talk given by a group of scientists who have been studying the Beech trees at Woodbury Castle for a project that has been running nearly 40 years. They have recorded the number of seeds produced by the Beech trees each year. Beech trees are known for periodically producing very large numbers of seeds in order to overwhelm "seed predators" such as squirrels and insects.

These high production years are followed by a couple of years of lower seed production. This strategy is known as "masting" and the high production years are known as mast years. Importantly, Beech trees are able to synchronously mast with each other so that the overwhelming effect on predators is maximised.

Recently, scientists have detected that Beech trees across the country are getting out of sync with each other. They have begun taking core samples from the trees in order to better understand why this might be happening. Interestingly our Beech trees at Woodbury Castle (some of which are over 200 years old) seem to be sticking together and masting on the same years. It will be interesting to see how this research develops!